Within a product portfolio, one finds an assortment of items that cover a variety of consumer needs and segments. There are probably some high and low performers. Perhaps there have been some changes to the market since the current portfolio strategy was defined. It’s even likely that pricing in the category has changed—perhaps driven by changes in cost of goods.

Faced with constantly changing markets, it’s necessary for a franchise to continuously re-evaluate its portfolio strategy in order to defend financial goals and positioning. Portfolio adjustments can have short-term and long-term consequences, so it’s important to consider the full range of options and potential costs and benefits to each. Here are some common strategic pitfalls that brand managers can run into when trying to optimize a portfolio.

Mistake #1: Becoming over-reliant on trade promotion.

Trade promotion is one of the largest drivers of volume in most fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) categories. Trade is very useful when applied in moderation. It can be quickly activated (especially temporary price reductions), and it often drives significant volume peaks. It is very visible, and because it is so close to the point of sale, it creates the feeling of a strong link between execution and sales. However, there are risks.

Consumers may become accustomed to a sustained promotion price and may revolt when prices return to their “everyday” price. Trade volume is often less incremental than it first appears. The product on promo may see a very strong lift in sales while on promotion, but this lift often comes at the expense of stealing volume from the other products within the portfolio, sometimes by downtrading consumers from higher-priced tiers. The other source of the lift in volume may be coming from consumers stocking up while something is on sale, effectively driving a short term bump that only borrows volume from the future.

Within the total cookie/cracker category, only 25 percent of promoted volume generates actual incremental volume. That is, 75 percent of the volume sold on deal would have sold regardless of the promotion, and the promotion only served to subsidize the purchase for the consumer. (Source: NielsenAK)

Addiction to pricing promotions can train consumers not to purchase until the product is on deal. The promotion becomes the de facto price. While it’s difficult to predict the long term effect of promotions using models, experience shows that it can bite brands down the road.

Mistake #2: Cutting off the incremental assortment tail

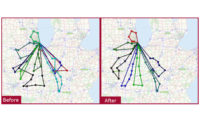

Getting rid of poor performing products in a portfolio is necessary to make room for new innovation on the shelf. However, the temptation is often to define performance by sales rate, and overlook how incremental the product is to the rest of the portfolio.

It’s usually a better strategy to delist the SKUs whose volume is most likely to flow back to the rest of the portfolio. For example, if you have two very similar products in your portfolio, then delisting one of them is likely to shift sales to the other one, the assumption being that both products fulfill the needs of the same consumers.

Most marketers are cognizant of the fact that adding a close-in line extension doesn’t gain a new audience; it largely cannibalizes the base business. What many overlook, however, is that incrementality is equally at play when delisting. Delisting a close-in line extension would have most customers flowing back to the base business. On the other hand, discontinuing a small but incremental platform would be costly and may result in losing consumers to competitors or from the category entirely.

If the brand/category manager needed to decide which of these sub-lines to de-list, a kneejerk reaction would be to delist chocolate milk because it has the lowest sales rate. However, its incrementality needs to be considered before doing so.

Mistake #3: Ignoring price thresholds

When a brand raises a price, there is a risk of losing sales, and when the price crosses a certain threshold the brand also risks losing sales. This psychological barrier is why many brands price at $1.99 rather than $2.00. This is relatively straightforward, and many marketers intuitively understand this.

However, it is easy to overlook the context of competitive pricing. There is absolute price and then there is your price compared to what the competition is offering; the difference is the “gap.”

No brand exists in a vacuum. In order for it to make sense for the retailer to execute a strategy, one has to consider the entire category, not just one brand standing alone. If a brand wants to implement a strategy, it’s important to consider the impact to the overall category. For example, increasing the price of a top seller might drive margin while sacrificing some unit sales. But increasing price too much might actually lead to fewer consumers walking down that aisle, hurting sales for the entire category. Before implementing a strategy, take a step back and think about the potential side effects.

While psychological whole dollar thresholds tend to be most prominent, elasticity also varies between these price points, often driven by how competition is priced.

Mistake #4: Forgetting who stands between you and your customer

CPG manufacturers often invest a great deal of time, money and resources building smart portfolio optimization, and then fail to consider their retailers’ priorities. When a manufacturer does pricing research, they too often think of the end customer as the customer—forgetting that the retailer is a key stakeholder standing in between. When that happens, you’ve just spent a lot of time strategizing around a model that is ultimately irrelevant.

A brand must consider how the changes to its portfolio impacts the overall category for the retailer. If one is able to create a scenario that benefits both one’s own franchise, as well as the overall category, it is more likely the retailer will implement your suggestion.

Mistake #5: Changing size without really considering value

In the eyes of the consumer, less is usually less. But sometimes it feels like more. Conventional wisdom tells us that any downsize without lowering price can leave people feel shortchanged. But sometimes a profit enhancing “downsize” can be framed as beneficial to the consumer, such as with convenience sizes.

Downsizing without considering the price/value proposition can lead to unexpected consumer backlash, especially if the change is visibly noticeable. It’s tempting to downsize in the hope that it’s less obvious to consumers than a price change. It also allows the product to stay within its promoted price group, simplifying implementation. At best, you risk consumers noticing the loss in value that comes from getting less product for the same price. At worst, customers may feel like they’ve been cheated.

However, if the brand is able to downsize while adding some other value to the consumer experience, customers may be happy to pay extra for the added benefits.

Within the snacking category, convenience packs often carry a higher price-per-pound than their corresponding base items. However, they provide benefits such as being easier to pack in a lunch bag or maintaining freshness for longer, so consumers happily pay the premium.

This phenomenon is not limited to only the snacking foods industry; coffee pods and devices are a popular trend despite costing many times more per serving than ordinary coffee grounds. The significant convenience factor of having a hot cup of coffee at the push of a button helps to justify the price differential.

The big takeaway: Think outside the box.

Each of these lessons comes down to one singular idea: Every action has potential unexpected consequences. Inside-the-box thinking happens when marketers fail to see beyond a single product, brand, portfolio, category or even their own P&L sheet. Armed with the right pricing insights, each of the strategies described above can lead to more robust portfolio management. Without them, negative consequences can ripple from the marketer’s desk to the customer’s shopping cart.

Anthony Kuo is manager, strategy, base business optimization, North America Confections for Mondelēz International. Oskar Toerneld is director and location manager at SKIM.