Call it an epiphany? Maybe. Life-changing? Most certainly. For Andrew Schuman, who had travelled across two-thirds of the country to visit Hammond’s Candies, the moment certainly struck a nerve.

“I had been networking with several colleagues about investing in a business,” he recalls. “I was looking to find a company that had untapped potential. I also wanted it to be a bit different.”

That scenario led him to Denver-based Hammond’s Candies in the fall of 2006.

At-a-Glance: Hammond’s Brands

Plants: 2 (Denver, 90,000 sq. ft.; Norfolk, 110,000 sq. ft.)

Brands: Hammond's Candies, Old Dominion, Mellow Snacks, Better Yet

Headquarters: Denver, Colorado

Sales: $40 million (Candy Industry estimate)

Employees: 300

Products: Hard candies, candy canes, lollipops, taffy, brittle, caramel, coated nuts, caramel corn, chocolate bars, chewy candies, cotton candy, marshmallow.

Management team: Andrew Schuman, ceo; Andrew Whisler, executive v.p. – marketing & business development; Steve Jordan, cfo and v.p. of finance and administration, Ralph Nafziger, cfo emeritus; Jeff Armbruster, v.p. of sales, John Anderson, v.p. of operations, Carla Paravicino, quality and safety manager; Victor Ortiz, kitchen manager

“I was getting a tour of the business with the existing owners when we walked into the back production area,” he says. “That day they were making a piece of candy that my grandmother always had in her candy dish. We called them Crystal Cuts, some people know it as rock candy.”

Boom. What kind of more relevant and emotional sign could one ask for?

In December of that year, at a family gathering in Maryland, Schuman announced that he was “buying the business” and that “we’re moving to Denver.” Well, the “we” included his wife and three children, at the time, ages 5, 7, and 8.

“Some people looked at me as if I was crazy. Others thought the challenge was impressive, uprooting my family and moving them clear across the country to take over a new business,” Schuman says. “When I look back, this was probably one of the more outlandish ideas I’ve had. I was so excited about the prospects the business offered and building a new life in Colorado, I never calculated how important my family was and the role it played in my life, a void that took a while to replace.”

What the entrepreneur had forgotten about were the benefits that come with having his sister and parents living just five miles away, in-laws a mere five hours by car, kids going to the same school, and being able to be a soccer coach for all his children.

“We didn’t know a soul in Denver,” he says. “And my children ended up going to three different schools.” With a little perseverance, the Schumans survived.

And what about the business you ask? Now, that’s another story worth telling. But let’s get back to the beginning.

Schuman, a University of Wisconsin-Madison graduate, had originally intended to pursue a career in real estate or investment banking. That dream got sidetracked because of his family business, a retail photofinishing chain known as MotoPhoto.

Having worked during high school and college in the family business, the collegiate grad found himself back at home and knee-deep in photofinishing, helping his father grow their business.

“We had 25-30 stores when I came into the business full time,” Schuman says. “I had no intention of staying. My father gave me a decent amount of responsibility and I learned from the ground up. I grew to love the business.”

By 2002, the Schumans had the most retail photofinishing shops in the MotoPhoto empire — 62 — which accounted for about $30 million in sales. Not too shabby for a father-and-son team. However, it was at this time that the digital camera made its debut. It didn’t take long for Schuman to realize the technological breakthrough would spell the end of photofinishing as they knew it.

“I told my dad that this wasn’t a viable business anymore,” he says. By 2010, they had two stores left. Father and son transitioned to a concept that Schuman says was ahead of its time, the shared office. Dubbed Your Office USA, it was a precursor to WeWork. The two eventually sold the business within two years.

It was then that Schuman turned his focus to locate an operating business that had intrinsic growth opportunities.

“I looked at health care, library services, and subscription-based businesses,” he recalls. “I wanted something that fit my personality. It wasn’t happening in the Washington D.C./Maryland area. That’s when I expanded my search to include other parts of the country.”

That search led to Denver, to Hammond’s, grandmother’s Crystal Cuts, to a holiday announcement, and to an April 2007 closing.

“We had challenges from Day 1,” he says. Although it was projected to do $7 million that year (2007), the company barely broke $4 million. Also, a major customer that was doing $800,000 in business with the company stopped doing so.

Unfortunately, that shaky first fiscal year for Schuman almost proved to be his undoing.

In July 2007, he realized that the company would not hit the $7 million sales number that was projected upon purchasing the business.

“We were built to be a company with a minimum of $7 million in revenue,” Schuman points out. Moreover, Hammond’s was a seasonal business, more so than most. “Thirty percent of our revenues comes in the month of October.” Cash flow resembles an extended drought and then a short but very intense monsoon. Banks often shy away from such financial models.

“We were in a very challenging position and I had to go back to my investors and raise additional capital,” he says.

Thanks to the influx of cash, Hammond’s Candies survived 2007. Now came the nitty-gritty work necessary to make the company first sustainable, then profitable.

“We needed to get to that $7-million sales mark,” Schuman says. “I came to the realization that the customers we had were not unlike what our stores were in the photo business. High-end, specialty retailers that needed the right products and attention. So we built programs that catered not only to our specialty customers, but for our major retailers as well.

“And our packaging wasn’t indicative of a candy company,” he adds. “It screamed that we were only a Christmas candy company.”

Thanks to Schuman’s experience in retailing, he was able to expand the company’s customer base. Thus, orders from such national companies as Whole Foods, Nordstrom’s, Dean & Deluca, Cracker Barrel and hundreds of local and regional specialty shops began to make an impact.

By 2009, the financials were beginning to improve. The following year — to modulate the peaks and valleys of being such a seasonal company — Schuman found an opportunity, purchasing McCraw’s Candies, manufacturers of a singular flat taffy.

That same year, he hired Andrew Whisler, who was formerly with Robert Rothschild Farms. A downsizing at the gourmet specialty food supplier led to Whisler changing industries and moving from Indiana to Denver. In making the move, he sent off an email to former brokers he had worked with informing them of the change.

Upon receiving the email, three brokers telephoned Schuman within five minutes of each other indicating he had to hire Whisler.

As Schuman relates, 25 percent of his time was spent with the broker network, a task he didn’t particularly enjoy. “I wasn’t very diplomatic with our brokers. They loved me as the owner, they were not fond of me as their national sales manager.”

More importantly, brokers liked Whisler. So the first day he came to work for Hammond, Whisler took over national sales. The brokers and Schuman welcomed the change.

Today, Whisler’s responsibilities as the company’s executive v.p. of marketing and business development encompass so much more than the national sales position he was hired for seven years ago.

“When Andy purchased the company, the previous ownership group had done a decent job of growing the company and brand awareness in the market, but he inherited a company that was too broad in SKUs, had very tired and basic branding and product pack sizes that were overly large for what consumers really needed,” Whisler explains.

“These factors were all taking a financial toll on the company. Immediate attention was given to reducing the product mix by 30 percent to only the best-selling products and a concerted three-year overhaul of the entire brand and packaging.”

As mentioned earlier, the company’s efforts to address the extreme seasonality — 75 percent or more of the yearly volume was shipping from August. 15-Nov. 15 — first came with the acquisition of McCraw’s Candies.

“This was a nice add-on for the company as the taffy sales were counter-cyclical to the holiday candies — so it helped ease cash flow through the summer months when rapid build-up for the holiday demand was in full swing,” Whisler says.

“We then identified areas of everyday opportunity such as the chocolate bar segment, caramel corn and cotton candy — chocolate bars and caramel corn being year-round steady sellers, and cotton candy being another counter cyclical spring/summer product,” he adds. “Today those three categories make up a significant percent of Hammond’s year-round revenue. These efforts all paid off, and for six years straight from 2010-2015, the company averaged yearly rates of annual growth in the 20 percent range.”

Such success enabled Hammond’s to make another acquisition in 2012, purchasing Old Dominion Peanut Co. in Norfolk, Va. Old Dominion Peanut is the nation’s largest manufacturer of peanut brittle and also has a range of other various nut candies. The move, Schuman explains, enabled Hammond’s to get into the “snack side of the business, a place where the market is growing rapidly.”

It also expanded the company’s distribution channels. Unlike Hammond’s specialty market venues, Old Dominion had access to the drug, mass, value and grocery channels, places Hammond’s had done little business in the past.

“We now have access to every channel in the market,” he says.

Currently, the company is in the process of consolidating the Norfolk locations into one manufacturing, processing, packaging and warehousing site. Upgrades are part of the planned consolidation, which is expected to be completed by early 2019.

But Schuman didn’t stop at peanut brittle and salted snacks. The diversification continued when Hammond’s launched chocolate bars in 2012.

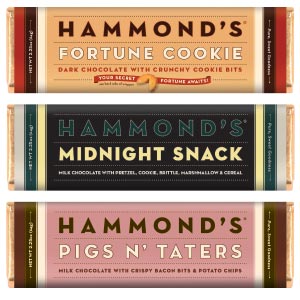

It was the first segment, Whisler says, “…that we saw could bring consistent year-round sales to the company. Our approach to the line was to have a mix of classic flavors that were already being sought out by consumers, such as Sea Salt Caramel, Cookie Dough and others, and complement it with a variety of bars in new/unique flavor mixes, Pigs n Taters, PB&J Sandwich, Midnight Snack to name a few.”

Well, the line took off, and it actually grew at a much faster rate than originally forecasted.

“We knew we couldn’t compete with the mass-manufactured national brands that are more of a commodity product, and Hammond’s is all about quality paired with excitement, so we didn’t want to focus on being super premium with single-origin beans and touting high cacao percentages,” Whisler explains. “We brought a high quality product that had a Belgian chocolate base and came up with unique flavor profiles at an affordable price [S.R.P. $2.99]. We were fortunate enough to win a few awards in this segment with our early creations, and the branding and quality has worked with our retailers and the consumers alike.”

But in the competitive confectionery industry, there’s no time to rest on successful new product launches; it’s always about what’s new.

“We have always tried to bring a range of ‘new’ to our mix each year, whether it’s new flavors within categories or new categories altogether,” Whisler says. “But you have to walk a fine line, as you can quickly find yourself spread too thin over too many products, which can have serious effects on operations and fulfillment.

“That being said, we like to keep the mix fresh and our consumers seeking out what’s new, so we are always working on new things to bring to the market while cutting other items that are trending off each year," he adds. We typically only do one launch per year in January, though some products are soft launches that end up becoming available for shipment later in the first quarter.”

Hammond’s kicked off 2017 with a new line of everyday snacking marshmallows. Mellow Fluffs are a play on one of Carl Hammond’s very first products when he founded the company in 1920, the Mitchell Sweet, a combination of marshmallow and caramel. With the growth in premium confections, specifically gourmet marshmallows, Hammond’s believes this is a segment that will also resonate with both retailers and consumers.

Demand for the hand-made, gourmet marshmallows has increased to the point where the company invested in an ultrasonic cutting machine as a means of adding capacity. The move enabled further growth in both branded and private-label sales of marshmallows.

“Heading into 2018, we have one of our most extensive new launches to date,” Whisler says. “What I am most excited about is that we are well on our way to launching a line of USDA-certified organic candies in our classic nostalgia Christmas candy line — a range of 16-20 products from candy canes to lollipops to mini ribbon and pillow candy gift bags.”

In addition, the company will also launch a better-for-you brand featuring three different products.

“We’re coming out with a 'better-for-you' product line that we believe will actually taste better than what is currently offered in the market,” Schuman says. “Our Better Yet line will feature nut-and-seed based products, chewy drops and a complimentary coated nut line,” Schuman says.

As he points out, the company now has three brands with a fourth on its way — Hammond’s, Old Dominion, Mellow Snacks and Better Yet — through which it can launch any type of new confection or snack product. To do so, as Schuman well knows, requires exacting execution.

“Besides new product development, we are currently focused on internal operations, on hitting our daily and weekly metrics that were set at the beginning of 2017,” he explains.

Victor Ortiz, kitchen manager for the company and a 16-year veteran, knows full well the challenges involved in scheduling, producing and shipping 200 different types of candies during the course of the year.

And it’s not just about meeting the daily poundage goal, it’s also about “finding solutions on the floor as they occur,” he says.

It is ongoing, as temperature and humidity fluctuations test even the most seasoned candy maker on any given day. That, coupled with assuring all SQF certification standards are met, involves constant monitoring.

As Carla Paravicino, quality and safety manager, points out, daily sampling as well as pre- and post-operational checks are standard at the plant. As she notes, “We encourage customers to come in and see our production facility.”

The company also encourages visitors for its daily tours. The 30-minute tour features a short film about the company followed by a guided hallway tour that allows visitors to view production through large picture windows.

Last year, the company had approximately 100,000 people view the way candies are made at the plant. The tour was ranked No. 3 by USA Today among all food and bakery tours in the United States. The average cash register ring at the factory retail shop ranged between $9 to $10. Tours, which take place every half hour, are free. Last year, the retail shop did in excess of $900,000.

Another revenue stream for Hammond’s is e-commerce. Schuman notes that it provides a nice base for the company, and he looks to jump-start the latent potential.

“Our focus for the last 10 years has been growing our wholesale business. We did not have the human capital to address a web strategy. However, this year we hired a full-time seasoned professional to manage our e-commerce and social media platforms,” he says. “The website will have a new look and feel come November.”

A decade since he acquired the company, Hammond’s has a new look and feel.

“We’ve made major changes to get to this point as a business,” Schuman says. But the work’s not done.

“We still have to make changes to position ourselves for success over the next 10 year,” he adds.

As evidenced, Schuman’s been there and he will be doing just that.